“I must create a system, or be enslav’d by another man's.”

― William Blake

I. The Happiness of Pursuit

For years, some of the world’s sharpest minds have been quietly turning your life into a series of games. Not merely to amuse you, but because they realized that the easiest way to make you do what they want is to make it fun. To escape their control, you must understand the creeping phenomenon of gamification, and how it makes you act against your own interests.

This is a story that encompasses a couple who replaced their real baby with a fake one, a statistician whose obsessions cost the US the Vietnam War, the apparent absence of extraterrestrial life, and the biggest FBI investigation of the 20th century. But it begins with a mild-mannered psychologist who studied pigeons at Harvard in the 1930s.

B. F. Skinner believed environment determines behavior, and a person could therefore be controlled simply by controlling their environment. He began testing this theory, known as behaviorism, mainly on pigeons. For his experiments, he developed the “Skinner box”, a cage with a food dispenser controlled by a sensor or button.

Skinner’s goal was to make his pigeons peck the button as many times as possible. From his experiments, he made three discoveries. First, the pigeons pecked most when doing so yielded immediate, rather than delayed, rewards. Second, the pigeons pecked most when it rewarded them randomly, rather than every time. Skinner’s third discovery occurred when he noticed the pigeons continued to peck the button long after the food dispenser was empty, provided they could hear it click. He realized the pigeons had become conditioned to associate the click with the food, and now valued the click as a reward in itself.

This led him to propose two kinds of reward: primary and conditioned reinforcers. A primary reinforcer is something we’re born to desire. A conditioned reinforcer is something we learn to desire, due to its association with a primary reinforcer. Skinner found that conditioned reinforcers were generally more effective in shaping behavior, because while our biological need for the primary reinforcer is easily satiable, our abstract desire for the conditioned reinforcer isn’t. The pigeons would stop seeking food once their bellies were full, but they’d take far longer to get tired of hearing the food dispenser click.

Skinner’s three key insights — immediate rewards work better than delayed, unpredictable rewards work better than fixed, and conditioned rewards work better than primary — were found to also apply to humans, and in the 20th Century would be used by businesses to shape consumer behavior. From Frequent Flyer loyalty points to mystery toys in McDonalds Happy Meals, purchases were turned into games, spurring consumers to purchase more.

Some people began to consider whether games could be used to make people do other things. In the 1970s, the American management consultant Charles Coonradt wondered why people work harder at games they pay to play than at work they’re paid to do. Like Skinner, Coonradt saw that a defining feature of compelling games was immediate reinforcement. Most of the feedback loops in employment — from salary payments to annual performance appraisals — were torturously long. So Coonradt proposed shortening them by introducing daily targets, points systems, and leaderboards. These conditioned reinforcers would transform work from a series of monthly slogs into daily status games, in which employees competed to fulfil the company’s goals.

In the 21st century, advances in technology made it easy to add game mechanics to almost any activity, and a new term — “gamification” — became a buzzword in Silicon Valley. By 2008, business consultants were giving presentations about leveraging fun to shape behavior, while futurists gave TED Talks speculating on the social implications of a gamified world. Underpinning every speech was a single, momentous question: if gamification could make people buy more stuff and work more hours, what else could it be used to make people do?

The tone was generally utopian, because back then gamification seemed to be mostly a force for good. In 2007, for instance, the online word quiz FreeRice gamified famine relief: for every correct answer, 10 grains of rice were given to the UN World Food Programme. Within six months it had already given away over 20 billion grains of rice. Meanwhile, the SaaS company, Opower, had gamified going green. It turned eco-friendliness into a contest, showing each person how much energy they were using compared with their neighbors, and displaying a leaderboard of the top 10 least wasteful. The app has since saved over $3 billion worth of energy. And then there was Foldit, a game developed by University of Washington biochemists who’d struggled for 15 years to discern the structure of an Aids virus protein. They reasoned that, if they turned the search into a game, someone might do what they couldn’t. It took gamers just 10 days.

Even established corporations saw gamification’s potential. In 2008, Volkswagen debuted a campaign called “The Fun Theory”, based on the idea that “fun is the easiest way to change people’s behavior for the better”. Piano stairs were installed at a Stockholm rail station to encourage people to use them instead of the escalator, leading to a 66% increase in stair use. Volkswagen also tried to gamify gamification itself, creating a contest for good game ideas. The winning idea was a “speedcam lottery”, where people who kept to the speed limit would be entered into a prize draw, funded by speeding fines.

It all seemed so simple: if we could only create the right games, we could make humanity fitter, greener, kinder, smarter. We could repopulate forests and even cure cancers simply by making it fun.

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. Instead, gamification took a less wholesome route.

We humans are harder to manipulate than pigeons, but we can be manipulated in many more ways, because we have a wider spectrum of needs. Pigeons don’t care much about respect, but for us it’s a primary reinforcer, to such an extent that we can be made to desire arbitrary sounds that become associated with it, like praise and applause.

Respect is so important to humans that it’s a key reason we evolved to play games. Will Storr, in his book The Status Game, charted the rise of game-playing in different cultures, and found that games have historically functioned to organize societies into hierarchies of competence, with score acting as a conditioned reinforcer of status. In other words, all games descend from status games. The association between score and status has grown so strong in our minds that, like pigeons pecking the button long after the food dispenser has stopped dispensing, we’ll chase scores long after everyone else has stopped watching.

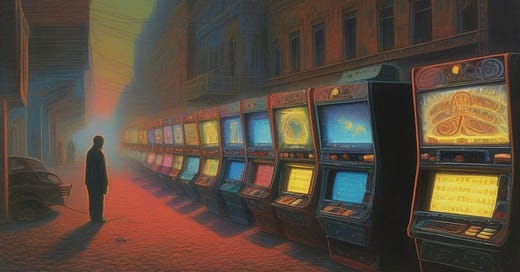

And so, when Facebook added “likes” in 2009, they quickly became a proxy for status, and a score to compete for. People now had a social stake in posting content. Hitting “send” became like activating a slot machine, initiating an excitingly uncertain outcome; the post might go completely unnoticed, or it might hit the jackpot and go viral, awarding the coveted prizes of respect and fame.

Other social media platforms followed, leveraging Skinner’s three laws to maximize button-pecking. They offered immediate reinforcement in the form of instant notifications, conditioned reinforcement in the form of “likes” and “followers”, and unpredictable reinforcement that varied with each post and each refresh of the page. These features turned social media into the world’s most addictive status game. And thus, just as pigeons were made to chase clicks, so eventually were we.

But this was just the beginning. Many in the managerial class saw the success of social media and wondered how they could use gamification for their own ends. The Chinese Communist Party was among the first to apply the principles of social media to the real world. In several towns and cities, it began trialing social credit schemes that assign citizens a level of “clout” based on how well they behave. In some areas, such as Rongcheng and Hangzhou, there are public signs that display leaderboards of the highest scoring citizens. The lowest scoring citizens may be punished with credit blacklists or throttled internet speeds.

Meanwhile, in the West, gamification is used to make people obey corporations. Employers like Amazon and Disneyland use electronic tracking to keep score of employees’ work rates, often displaying them for all to see. Those who place high on the leaderboards can win prizes like virtual pets; those who fall below the minimum rate may be financially penalized.

Game features are even more pervasive in the digital world. In little over a year, the Chinese shopping app Temu has exploded in popularity thanks to its “play to pay” model: as users browse deals they’re presented with puzzles to solve, roulette wheels to spin, and challenges to complete, which reward them with credit and special offers. Unsurprisingly, users are now spending twice as much time on Temu than on Amazon.

Gamification has also transformed dating apps. Zoosk works like a typical role-playing game, where you gradually accumulate “experience points”, which unlock new abilities, such as animated virtual gifts to send to prospective dates. Meanwhile, on Tinder you can purchase various “level-ups” — Boosts, Super Likes, and Rewinds — that increase your chances of winning and compel you to keep playing to get your money’s worth. And if you have no luck on dating apps, there are always AI girlfriends to play with: apps like iGirl and Replika award users points for their commitment, which can be used to “level up” their virtual lovers into a version that is more intimate.

These are only a few examples. Almost every kind of app, from audiobook apps to taxicab apps to stock trading apps, now employs game mechanics like points, badges, levels, streaks, progress bars, and leaderboards. Their ubiquity attests to their success in hooking people.

Gamification once promised to create a better society, but it’s now used mainly to addict people to apps. The gamifiers, like Skinner’s pigeons, prioritized immediate rewards over delayed ones, so they gamified for the next financial quarter and not for the future of civilization.

So where does this all lead? What is the endgame?

II. A Maze Called Utopia

At the University of Michigan in the mid-twentieth century, there was a zoologist named James V. McConnell. A strong believer in fun, he often presented his academic research alongside satire and poetry, so it was difficult to tell which was which, a habit that made him popular with students but unpopular with his fellow professors.

One of the few things McConnell took seriously was behaviorism. He was transfixed by Skinner’s work on pigeons, and wished to expand the work to humans, with an eye to creating a perfect society. In a 1970 Psychology Today article he wrote:

We should reshape our society so that we all would be trained from birth to want to do what society wants us to do. We have the techniques now to do it. Only by using them can we hope to maximize human potentiality.

In short, he wanted to turn society into a Skinner box.

Throughout the Seventies, McConnell used Skinnerian techniques to create rehabilitation programs for prisoners and psychiatric patients, some of which were successful. But his most ambitious scheme emerged in the early Eighties, when he witnessed people being captivated by video games like Donkey Kong and Pac Man, and realized their addictive mechanics could be translated to other, more productive activities. He pitched an ambitious project to gamify education to tech companies like Microsoft and IBM, but he was 30 years too early, and they couldn’t yet see its promise. There was, however, one person who’d taken a keen interest in McConnell’s work. His name was Ted Kaczynski.

Kaczynski was an awkward but gifted student, coldly matter-of-fact in manner, for which he was described by his schoolmates as a “walking brain”. In a school IQ test he’d scored 167 (140 is considered “genius”).

He’d come to Michigan in 1962 as a postgraduate from Harvard, where he’d studied mathematics and graduated at just 18. But at Harvard, he’d also been subjected to torturous experiments. In a lab not far from where Skinner had once experimented with pigeons, psychologists linked to US intelligence were now experimenting with humans — one of whom was Kaczynski. Under the glare of blinding lights, he was methodically humiliated to see how he reacted. He claimed the experience didn’t affect him, and yet, within just a few years, he’d developed an intense paranoia about psychological conditioning. And so, when Kaczynski learned of McConnell’s proposals to create a utopia through behavior modification, he concluded that the jocular professor was an existential threat to humanity, and that he needed to die.

It wasn’t a decision Kaczynski had made lightly; he’d developed an entire philosophy to justify it. Influenced by techno-dystopian writers like Aldous Huxley and Jacques Ellul, Kaczynski believed the Industrial Revolution had turned society into a cold process of production and consumption that was gradually crushing everything humans valued most: freedom, happiness, purpose, meaning, and the ecosystem. In his view, everything society produced — including science and technology — served industry, not humanity, and was therefore increasingly purposed not to help us but to condition us so we wouldn’t resist what was being done to us and the earth.

In short, where society had once been shaped to accommodate people, now people were being shaped to accommodate society. And this misshaping was destructive because it conflicted with our deepest nature.

Kaczynski believed modern society made us docile and miserable by depriving us of fulfilling challenges and eroding our sense of purpose. The brain evolved to solve problems, but the problems it had evolved for were now largely solved by technology. Most of us can now obtain all our basic necessities simply by being obedient, like a pigeon pecking a button. Kaczynski argued that such conveniences didn’t make us happy, only aimless. And to stave off this aimlessness, we had to continually set ourselves goals purely to have goals to pursue, which Kaczynski called “surrogate activities”. These included sports, hobbies, and chasing the latest product that ads promised would make us happy.

For Kaczynski, the result of reorienting our lives to chase artificial goals was that we became increasingly dependent on society to provide us with them. And without our own inherent sense of purpose, we’d inevitably be made to chase goals that were good for the industrial machine but bad for us.

Kaczynski’s theories eerily prophesize the capture of society by gamification. While he overlooked the benefits of technology, he diligently noted its dangers, recognizing its role in depriving us of purpose and meaning. Today the evidence is everywhere: religion is dying out, Western nations are culturally confused, people are getting married less and having fewer children, and many jobs are threatened by automation, so the traditional pillars of life — God, nation, family, and work — are weakening, and people are losing their value systems. Amid such uncertainty, games, with their well-defined rules and goals, provide a semblance of order and purpose that may otherwise be lacking in people’s lives. Gamification is thus no accident, but an attempt to plug a widening hole in society.

Unfortunately, it seems to be only a band-aid. Kaczynski observed that surrogate activities rarely kept people contented for long. There were always more stamps to collect, a better car to buy, a higher score to achieve. He believed artificial goals were too divorced from our actual needs to truly satisfy us, so they merely served to keep us busy enough not to notice our dissatisfaction. Instead of a fulfilled life, a life filled full.

Today, people increasingly live inside their phones, bossed around by notifications, diligently collecting badges and filling progress bars, even though it doesn’t make them happy. On the contrary, substantial research comprising over a hundred studies finds that prioritizing extrinsic goals over intrinsic goals — in other words doing things to win prizes and achieve high scores rather than for the inherent love of doing them — leads to lower well-being.

Kaczynski seemed to recognize this long before smartphones emerged. He felt that building a life around chasing what was offered on billboards and in magazines wouldn’t make him happy, and would only feed the Machine, so in 1971 he fled society, holing himself up in a log cabin in the Montana wilderness. There he attempted a simple and self-sufficient life, enjoying the small things like the sound of birds singing and the feeling of sunrays on his back.

But this idyll wouldn’t last. He claims that while hiking across one of his favorite spots — a rocky ridge with a waterfall — he was aghast to find a road had been built through it. As he saw it, industrialization, like some fungus creeping across the world, had followed him even here. Enraged, he decided modernity couldn’t be escaped, and had to be destroyed.

His emotional instability got the better of him, and in 1978 he began posting homemade bombs to those he accused of betraying humanity. In 1985, a package arrived at McConnell’s home. It was opened by his assistant, Nicklaus Suino. The package only partially exploded, injuring Suino and McConnell, and leaving them both shaken for life.

They were lucky. Less than a month later, Kaczynski would send another, more carefully prepared bomb to computer store owner, Hugh Scrutton, who’d become Kaczynski’s first murder victim.

By then, the FBI’s investigation into the bombings had grown into the largest in its history. For over a decade they scoured the country as Kaczynski continued to kill and injure, but much of their time was wasted chasing mirages, for Kaczynski would often scatter his bomb parcels with red herrings such as notes referencing fictitious conspiracies and signed with made-up initials.

Kaczynski’s actions, though unforgivable, can teach us as much about gamification as his philosophy. His red herrings lured people away from what they actually sought, and, as we shall see, this is the greatest danger of gamification.

III. When Red Herrings Become White Whales

While Kaczynski wanted to demolish industrial society and return humanity to an agrarian life, US defense secretary Robert McNamara wanted the opposite: to use American industrial might to crush the agrarian society of Vietnam.

McNamara was a statistician who believed what couldn’t be measured didn’t matter. He charted progress in the Vietnam war by body count, because it was simple to measure. It was his way of keeping score. But his focus on what could be easily measured led him to overlook what couldn’t: negative public opinion of the US Army both at home and in Vietnam, which deflated US morale while boosting enemy conscription. In the end, the US was forced to withdraw from the war, despite winning the battle of bodies, because it had lost the battle of hearts and minds.

Thus, the McNamara fallacy, as it came to be known, refers to our tendency to focus on the most quantifiable measures, even if doing so leads us from our actual goals. Put simply, we try to measure what we value, but end up valuing what we measure.

And what we measure is rarely what we mean to value. As Skinner showed, the goals of games — points, badges, trophies — are secondary reinforcers that only derive their worth due to their association with something we actually desire. But these associations are often illusory. A click is not the same thing as a food pellet. And points are not the same as progress.

We’re easily motivated by points and scores because they’re easy to track and enjoyable to accrue. As such, scorekeeping is, for many, becoming the new foundation of their lives. “Looksmaxxing” is a new trend of gamified beauty, where people assign scores to physical appearance and then use any means necessary to maximize their score. And in the online wellness space, there is now a “Rejuvenation Olympics” complete with a leaderboard that ranks people by their “age reversal”. Even sleep has become a game; many people now use apps like Pokemon Sleep that reward them for achieving high “sleep scores”, and some even compete to get the highest “sleep ranking”.

Most such scores are simplifications that don’t tell the whole story. For instance, sleep trackers only measure what’s easy to measure, like movement, which says nothing about crucial facts like time spent in REM sleep. A more accurate measure of how well you slept would be how refreshed you feel in the morning, but since this can’t be quantified, it tends to be ignored.

Further, if increasing one’s youthfulness score requires a daily 2-hour skincare routine, a diet of 50 pills each morning and night, abstention from many of life’s pleasures, and constant fixation on one’s vital metrics, is it really worth it? Of what value is adding a few years to your life if the cost is a life worth living? The scores we use to chart progress can’t articulate the nuances of reality, and yet we often tie our life goals and even self-worth to such arbitrary numbers.

In the end, even Kaczynski, with his IQ of 167, was led astray by red herring goals. In 1995 he enacted his endgame, demanding the New York Times and Washington Post print his anti-technology manifesto to prevent further bloodshed. All along, his goal had been to get the widest possible newspaper coverage, to maximize how many people would see his manifesto, but like McNamara he didn’t account for what couldn’t be quantified, such as how people would see his manifesto. Skinner’s pigeons had learned to desire the click of the food dispenser because it had been accompanied by food, and Kaczynski’s intended audience learned to hate his arguments because they’d been accompanied by violence. By maximizing audience size at the expense of everything else, Kaczynski gained a massive audience unwilling to give him a fair hearing.

Further, his manifesto contained a peculiar choice of words (“eat your cake and have it”), which was recognized by his brother, David, who alerted the police, leading to Kaczynski’s capture. And so, by fixating on the most obvious metric — the size of his audience — Kaczynski lost the one thing he’d been fighting for all along: freedom.

Kaczynski played the wrong game, and was trapped by it. Today, we all face similar traps. We chase numbers and icons because they’re always available, and the chase is often so immersive that it keeps us from seeing where it leads, which is often far away from what we actually want. This can lead to what the evolutionary psychologist Diana Fleischman calls “counterfeit fitness”: the constant, momentary “wins” that come with playing digital games give us a false sense of progression and accomplishment, a neurochemical high that feels like victory but is not, and which, if it becomes a habit, risks lulling us out of pursuing true fulfilment.

It explains why so many young men have lost themselves in video games, and are no longer in employment or relationships. The false signals they’re getting from video game progress, combined with the sexual reward of online porn, are convincing their dopamine pathways that they’re winning in life, even as their minds and futures atrophy.

It’s easy to persuade people into tying their sense of progress to fake or trivial goals. Casinos keep their customers happily losing money by distracting them with minor side games they’re likely to win. The small victories convince them they’re winning overall even as they lose the only games that actually matter.

This strange quirk of human behavior can even cost lives. In South Korea, a young couple became so addicted to raising a virtual baby that they let their real baby starve to death. The parents prioritized what they could quantify — levelling up their virtual baby — over that which they couldn’t — the life of their real one.

What makes pathological gameplaying so dangerous is that the more harm it does, the more alluring it becomes. If your baby is dead, why not raise a virtual one? If your life of playing video games has stopped you finding a girlfriend, why not play the AI girlfriend game? Thus, bad games form a feedback loop: they distract us from pursuing the things that will bring us lasting contentment, and without this lasting contentment, we become ever more dependent on false, transient metrics like scores and leaderboards to imbue our lives with meaning.

All the things a gamified world promises in the short term — pride, purpose, meaning, control, motivation, and happiness — it threatens in the long term. It has the power to detach people from life itself, rewriting their value systems so they favor the recreational over the real, and the next moment over the rest of their lives.

So what’s the solution?

IV. Playing for Keeps

There are billions of habitable planets in our galaxy, and many of them are far older than our own. Statistically, this would suggest that by now our galaxy would be teeming with signs of advanced alien life. And yet space is silent. This discrepancy, known as the Fermi paradox, has puzzled scientists for almost a century. Ted Kaczynski believed his prophecies offered an answer.

While serving a life sentence in jail, Kaczynski wrote a little-known sequel to his manifesto, entitled “Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How”. In it he outlines his belief that all technologically advanced civilizations become trapped in fatal games before they learn to colonize space. This happens because industry is driven by competition, and competition favors short-term wins over long-term sustainability, because players who care about long-term sustainability are significantly disadvantaged compared to players who only care about winning.

To illustrate his point, Kaczynski describes a thought experiment involving a forested region occupied by several rival kingdoms. The kingdoms that clear the most land for agriculture can support a larger population, affording them a military advantage. Every kingdom must therefore clear as much forest as possible, or face being conquered by its rivals. The resulting deforestation eventually leads to ecological disaster and the collapse of all the kingdoms. Thus, a trait that is advantageous for every kingdom’s short-term survival leads in the long term to every kingdom’s demise.

Kaczynski was describing a “social trap”, a term coined by a student of Skinner, John Platt, who’d theorized that an entire population behaving like pigeons in a Skinner box, each acting only for the next immediate reward, would eventually overexploit a resource, causing ruin for everyone. What Platt called “social traps”, Kaczynski called “self-propagating systems”, because he viewed them as negative-sum games that took on a life of their own, defeating every player to become the only winner. He believed such games not only drove industrialization but also replaced the sense of purpose and meaning that industrialization destroyed. They were thus inextricable from technological advancement, and, in a society like ours, impossible to stop.

In jail, Kaczynski was forbidden access to the web, and in letters he struggled to understand what Facebook was. Nevertheless, his warnings could easily have been referring to social media.

On Instagram, the main self-propagating system is a beauty pageant. Young women compete to be as pretty as possible, going to increasingly extreme lengths: makeup, filters, fillers, surgery. The result is that all women begin to feel ugly, online and off.

On TikTok and YouTube, there is another self-propagating system where pranksters compete to outdo each other in outrageousness to avoid being buried by the algorithm. Such extreme brinkmanship frequently leads to arrest or injury, and has even led to the deaths of, among others, Timothy Wilks and Pedro Ruiz.

On X, meanwhile, there is a self-propagating system known as “the culture war”. This game consists of trying to score points (likes and retweets) by attacking the enemy political tribe. Unlike in a regular war, the combatants can’t kill each other, only make each other angrier, so little is ever achieved, except that all players become stressed by constant bickering. And yet they persist in bickering, if only because their opponents do, in an endless state of mutually assured distraction.

Those are just three examples of social traps that have emerged in our gamified age. But the most worrying social trap is gamification itself.

Companies that exploit our gameplaying compulsion will have an edge over those who don’t, so every company that wishes to compete must gamify in ever more addictive ways, even though in the long term this harms everyone. As such, gamification is not just a fad; it’s the fate of a digital capitalist society. Anything that can be turned into a game sooner or later will be. And the games won’t just be confined to our phones — “extended reality” eyewear like Meta Quest and Apple Vision, once they become normalized, will make playing even harder to avoid.

Games will be created not just to extract money from people, but also data. The 2025 Enhanced Games, for instance, is a new futuristic version of the Olympics, funded by tech moguls like Peter Thiel, where contestants can exploit anything from cybernetic implants to PEDs to get a competitive advantage. The purpose of the games seems to be transhumanist: to motivate people to discover new ways to augment human abilities, with the eventual goal of turning men into gods.

There is, after all, a vacancy in heaven. When God is dead, and nations are atomized, and family seems burdensome, and machines can beat us at our jobs and even at art, and trust and truth are lost in a roiling sea of AI-generated clickbait — what is left but games?

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Games can motivate us to destroy ourselves, but they can also motivate us to better ourselves. In a gamified world, it’s possible to play without getting played, if one only chooses the right games. As Liv Boeree said: “Intelligence is knowing how to win the game. Wisdom is knowing which game to play.” Not playing is not an option; if you don’t play your own games, you’ll inevitably play someone else’s. So how do you decide which games to play? The story of gamification offers five broad rules.

First: choose long-term goals over short-term ones. Short, frequent feedback loops offer regular reinforcement, which helps motivate us. But what is made to motivate us too often addicts us. So consider the long-term outcomes of the games you’re playing: if you did the same thing you did today for the next 10 years, where would you be? Play games the 90-year-old you would be proud of having played. They won’t care how many progress bars you filled; they will care how many times you saw your parents.

Second: choose hard games over easy ones. Since the long-term value of games lies in their ability to hone skills and build character, easy games are usually a trap. People with unearned wealth — thieves, heirs and lottery winners — often end up losing it all, because the struggle to obtain a reward teaches us the reward’s worth, and is thus a crucial part of the reward.

Third: choose positive-sum games over zero-sum or negative-sum ones. Games evolved to confer status, and status is zero-sum — for some to have it, others must lose it. But we no longer have to play such games; we can change the rules so a win for me doesn’t mean a loss for you. Educational games are one example. Wealth creation is another. Positive-sum games — where every player benefits by playing — are a form of competition that brings people together instead of driving them apart.

Fourth: choose atelic games over telic ones. Atelic games are those you play because you enjoy them. Telic games are those you play only to obtain a reward. Chasing rewards like trophies and leaderboard rankings can help drive us to succeed, but a fixation on such rewards can become a source of stress, and can even make leisure activities feel like drudgery, turning games into work.

Finally, the fifth rule is to choose immeasurable rewards over measurable ones. Seeing numerical scores increase is satisfying in the short term, but the most valuable things in life — freedom, meaning, love — can’t be quantified.

There are an overwhelming number of games to choose from. If you want to keep fit, try Zombies, Run!, an app that takes the form of a post-zombie-apocalypse radio broadcast telling you which direction to run to avoid being eaten. If you want to learn general knowledge while helping those in poverty, play the FreeRice quiz. And if you want to form good habits, there’s Habitshare, which lets your friends track your attempts, motivating you more than if you were only accountable to yourself.

But if, among the countless games out there, you can’t find one right for you, then you can just create your own. Fun is not the pursuit of happiness, but the happiness of pursuit, and literally anything can be pursued. By now there’s a way to keep any kind of score and play any kind of game.

Kaczynski’s game is over; he committed suicide last summer, still adamant humanity was doomed. His fearful legacy has since passed to his disciples, like Liverpool man Jacob Graham, who was recently jailed for terrorism after trying to emulate his idol. Graham may have thought he was saving the world, but, with all his talk of maximizing kill counts, he too was just playing a bad game.

In the end, Kaczynski and his followers made the same mistake as Skinner: they viewed us as mere puppets of our environment, devoid of agency and the ability to adapt. They needn’t have feared the world becoming a Skinner box, because, among all the papers written about that troublesome contraption, one fact is always overlooked: Skinner’s pigeons only kept pecking the button because they were trapped in a cage — they had nothing else to do. But you are still free. Even in a world where everything is a game, you don’t have to play by other people’s rules; you have a wide open world to create your own.

Your move.